Samlingssida om de svenska studierna om Pierre Fermat med introduktionslektionen till den naturvetenskap som är grunden till LaRouches fysiska ekonomi. Ett första kurstillfälle hölls i Fruängen den 30 januari 2025 som blev en bra introduktion till dessa studier.

Studier i fysisk ekonomi: Pierre Fermats strid med Descartes om ljuset introduktion med Elias Dottemar, Ulf Sandmark och Kjell Lundkvist, Schillerinstitutet den 30.1.2025 Se video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTutuNnyrVI

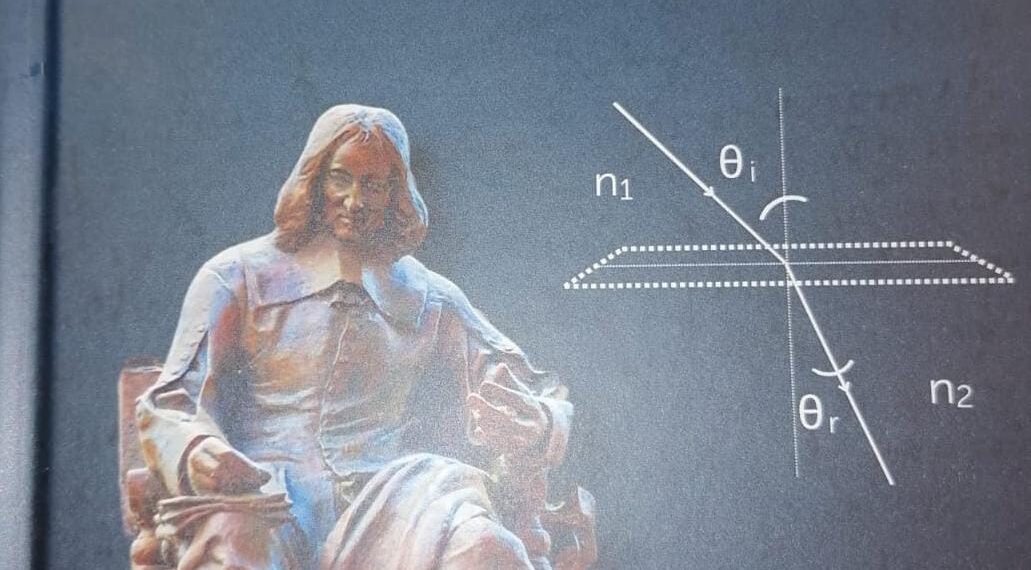

Introduktion till studier i den naturvetenskap som är grunden till LaRouches fysiska ekonomi. Ett första kurstillfälle hölls i Fruängen den 30 januari 2025 som blev en bra introduktion till dessa studier. Det handlar om Pierre Fermats genombrott för förståelse om ljuset och naturens val att alltid finna bästa vägen. En kurs om detta har just genomförts i New Jersey, USA, under ledning av Jason Ross, Schillerinstitutets koordinator för vetenskap. Han har just givit ut en bok på Amazon där han mycket pedagogiskt går igenom breven från 1600-talet där den franske forskaren Pierre Fermat utmanade den store René Descartes vilket blev en mycket åskådlig filosofisk uppgörelse om grunden för vetenskap. Det ledde vidare till Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz och hans forskningsgenombrott för fysik, matematik och ekonomi. Det finns videor på de fyra amerikanska lektionerna: • Fermat on the Narrow Path

Länk till videor på de fyra amerikanska lektionerna: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLS-Tvr0ip9TfoHxsMtnqF8ixdVCWteXh_&si=SZKQlijRQuhGSTe5

Elias Dottemar visar fiskarens synvilla.

Elias Dottemar visar fiskarens synvilla.

I lektionen medverkade Elias Dottemar, Ulf Sandmark och Kjell Lundkvist

I lektionen medverkade Elias Dottemar, Ulf Sandmark och Kjell Lundkvist

Ett efterord och recension på engelska av Jason Ross´ bok publicerades i EIR: Book Review: Pierre Fermat: Ending the Tyranny of Descartes and the Cartesians by Pierre Bonnefoy. A review of The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes: A Sourcebook on Pierre de Fermat’s Principle of Least Time, transl. & ed., Jason A. Ross. https://larouchepub.com/other/book_reviews/2024/5150-pierre_fermat_ending_the_tyran.html

Slaget om ljuset: Fermat vs. Descartes

En bok med de ursprungliga breven om Pierre de Fermats princip om minsta möjliga tid

Av Jason Ross, redaktör och översättare introduktör.

Här följer en automatöversättning till svenska av detta efterord och recension som även är utskriven nederst här på engelska:

Pierre Fermat: Slut på Descartes och cartesianernas tyranni

av Pierre Bonnefoy

Artikel i EIR 22 november 2024 Utskrift av denna artikel finns nederst i dokumentet på engelska:

EIR den 12 december – Vi publicerar här, med tillstånd, efterordet till boken av Jason Ross The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes, En bok med de ursprungliga breven om Pierre de Fermats princip om minsta tid. Pierre Bonnefoys efterord är en mästerlig sammanfattning av boken som går utöver en ren recension, som placerar Fermats arbete mitt i striden inom vetenskapen vid den tiden och lägger fram hur den ledde fram till senare upptäckter av Christiaan Huygens och Gottfried Leibniz som byggde på Fermats vetenskapliga genombrott.

The Battle for Light är den första omfattande engelska översättningen av Fermats fullständiga korrespondens om ljus, med hans banbrytande dispyter med René Descartes, vars förklaring av ljusets brytning Fermat inte alls fann övertygande. Den presenterar Fermats fullständiga korrespondens om ljus, tillsammans med René Descartes uppsats ”Dioptrics” och arbetet med Marin Cureau de la Chambre, vars idé om ”minsta avstånd” katalyserade Fermats formulering av minsta tid.

Ross översättningar, som presenteras tillsammans med sitt historiska sammanhang, ger en fascinerande inblick i de debatter som formade den fysiska vetenskapens framsteg. Ross bok med de ursprungliga breven innehåller också Fermats banbrytande arbete med att hitta minima och maxima – vilket gjorde det möjligt för honom att exakt beräkna de brytningsvinklar som genererades av hans princip om minsta tid, och som var en viktig inspirationskälla till Leibniz´ utveckling av infinitesimalkalkylen.

av Pierre Bonnefoy

När min vän Jason Ross bad mig att skriva efterordet till hans bok om den grundläggande filosofiska och vetenskapliga strid som ägde rum i mitt land, Frankrike, för nästan fyra århundraden sedan, tackade jag ja med stor glädje, eftersom denna uppgift gör det möjligt för mig att samtidigt belysa att inte alla fransmän förtjänar det dåliga rykte som ibland tillskrivs dem – att de alla är cartesianer. Tvärtom har några av mina berömda landsmän kämpat mot cartesianismen, som vi har sett på de föregående sidorna.

Den historiska kontexten: Fermat vs. Descartes

Grälet mellan Pierre Fermat (1601-1665) och René Descartes (1596-1650), som Ross har avslöjat i detta arbete genom att förlita sig på originaltexter, representerar en viktig historisk episod som gjorde 1600-talets Frankrike till vetenskapens fyrbåk i Europa. Detta återspeglades bland annat i Jean-Baptiste Colberts (1619-1683) grundande av Académie des Sciences i Paris 1666 (Franska vetenskapsakademin). Colbert, som var intelligentare än många av dagens västerländska politiker, insåg värdet av att samla forskare globalt och överbrygga politiska skiljelinjer.

Att bara samla vetenskapsmän garanterar dock inte en skörd av upptäckter; det måste också finnas ett ärligt sökande efter sanningen i deras ömsesidiga interaktioner. Detta kräver ett visst mod – mod att stå upp när man inser att alla ens kollegor har fel i en fråga. Att vara ärlig i en sådan miljö innebär att våga konfrontera det heliga ”vetenskapliga samförståndet”.

I själva verket uppstår detta problem i alla tider och på alla platser – inklusive i vår egen tid. Men det är osannolikt att den franska vetenskapen skulle ha kunnat spela sin ledande roll om inte några särskilt modiga individer, bland vilka Fermat framstår som en pionjär, hade vågat angripa de vetenskapliga dogmer som Descartes och cartesianerna hade infört. Bland dessa personer måste vi särskilt nämna Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), som upprätthöll en vänskaplig och vetenskaplig korrespondens med Fermat, även om de aldrig träffades; holländaren Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), som ledde Colberts Académie des Sciences; och tysken Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), som genom att bygga vidare på sina föregångares upptäckter åstadkom en vetenskaplig revolution genom att uppfinna differentialkalkylen.

Detta återspeglades bland annat i Jean-Baptiste Colberts (1619-1683) grundande av Académie des Sciences i Paris 1666. Colbert, som var intelligentare än många av dagens västerländska politiker, insåg värdet av att samla forskare globalt och överbrygga politiska skiljelinjer.

Att bara samla vetenskapsmän garanterar dock inte en skörd av upptäckter; det måste också finnas ett ärligt sökande efter sanningen i deras ömsesidiga interaktioner. Detta kräver ett visst mod – mod att stå upp när man inser att alla ens kollegor har fel i en fråga. Att vara ärlig i en sådan miljö innebär att våga konfrontera det heliga ”vetenskapliga samförståndet”.

I själva verket uppstår detta problem i alla tider och på alla platser – inklusive i vår egen tid. Men det är osannolikt att den franska vetenskapen skulle ha kunnat spela sin ledande roll om inte några särskilt modiga individer, bland vilka Fermat framstår som en pionjär, hade vågat angripa de vetenskapliga dogmer som Descartes och cartesianerna hade infört. Bland dessa personer måste vi särskilt nämna Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), som upprätthöll en vänskaplig och vetenskaplig korrespondens med Fermat, även om de aldrig träffades; holländaren Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), som ledde Colberts Académie des Sciences; och tysken Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), som genom att bygga vidare på sina föregångares upptäckter åstadkom en vetenskaplig revolution genom att uppfinna differentialkalkylen. Men Ross bok visar oss att om Descartes verkligen hade upptäckt denna lag, skulle vi kunna dra slutsatsen att han själv inte var en praktiserande cartesian! De ”förklaringar” han gav till fenomenet är faktiskt så fantasifulla att vi förstår att de har lagts till i efterhand till en redan etablerad matematisk lag: han kom inte fram till den korrekta matematiska formeln genom avdrag från uppenbara sanningar, som hans metod föreskriver. Vi måste dra slutsatsen att refraktionens sinuslag troligen fastställdes av Willebrord Snell (1580-1626), som Descartes hade känt i Holland; Snell kunde inte göra anspråk på den för sig själv, eftersom han dog innan Descartes publicerade sin Dioptrique (Dioptrics), den första boken som anger den.

Fermat däremot använde sig inte av cartesiansk deduktion utan av den experimentella metoden.

Den går ut på att man först formulerar en allmän hypotes och sedan testar den genom ett nytt experiment: Om experimentets resultat motsäger hypotesen, måste hypotesen överges och en annan sökas; om experimentet bekräftar hypotesen, kommer den att behållas för att utveckla en ny teori. Naturligtvis kommer denna nya teori att antas endast så länge som den inte i sin tur ogiltigförklaras av ett annat experiment. Den experimentella metoden bygger med andra ord inte på något uppenbart i sig självt – bara på den hypotes som forskaren föreställer sig – men den utgör en verklig satsning på framtiden: Forskaren hoppas att resultatet av experimentet kommer att överensstämma med vad hans hypotes förutspådde.

Principen om minsta tid

När det gäller ljuset ställde Fermat upp en hypotes om minsta möjliga tid, enligt vilken ljuset minimerar den tid det tar att färdas från en given punkt till en annan. Fermat fann att denna hypotes stämde överens med den redan experimentellt verifierade sinuslagen för ljusbrytning, vilket gav honom betydande tyngd gentemot cartesianerna, som inte hade någon egen trovärdig teori. Det är intressant att notera att det experiment som slutgiltigt bekräftade Fermats hypotes utfördes långt efter både Fermats och Descartes död. Enligt Fermat färdas ljuset lättare och snabbare i mindre täta medier och långsammare i tätare medier, medan Descartes menade att det var tvärtom. Eftersom 1600-talets teknik inte kunde jämföra ljusets hastighet i olika medier överlät Fermat åt framtida generationer att avgöra om han skulle välja Descartes eller Fermat. På 1800-talet gav Foucaults experiment Fermat rätt: ljuset är faktiskt snabbare i luft än i vatten. Cartesianerna hade dock utövat en sådan intellektuell terror mot vetenskapssamhället att Fermats seger inom optiken inte räckte för att störta deras hegemoni.

Pascals experiment om vakuum

Andra segrar var nödvändiga, bland annat Pascals med sina experiment om vakuum. Tänk dig ett genomskinligt provrör, minst 760 mm långt, som är helt fyllt med kvicksilver. Det vänds sedan upp och ner så att öppningen hamnar i en bassäng som också innehåller kvicksilver. I detta experiment, som förebådar uppfinningen av barometern, ser man hur kvicksilvret sjunker ner i provröret och bildar en kolonn som når en viss höjd över kvicksilverytan i bassängen. Frågan som då hemsökte forskarna var: ”Vad finns i röret mellan toppen av kvicksilverpelaren och slutet av röret?”

En kontrovers uppstod genom korrespondens mellan Pascal, som hade utfört en rad experiment inklusive detta, och en jesuitpater vid namn Étienne Noël, som hade varit lärare till Descartes och ifrågasatte Pascals tolkning av sina observationer.

Noël, liksom Descartes, baserade sina argument på en till synes obestridlig sanning: ”Naturen avskyr vakuum”. Därför kunde det inte finnas något vakuum i röret ovanför kvicksilvret, och därför måste utrymmet innehålla någon form av substans. Nu var det ”känt” på den tiden att det bara fanns fyra elementära ämnen: jord, vatten, luft och eld. Därför kunde ämnet i röret bara vara en förening av dessa ämnen, eller ett av dem. Därför måste detta ämne vara luft.

Därför kan ämnet i röret bara vara en förening av dessa ämnen, eller ett av dem. Därför måste detta ämne vara luft. Denna luft erbjöd dock inget motstånd mot kompression, eftersom man genom att luta röret tillräckligt kunde se det ge vika för kvicksilvret tills det försvann, och se det dyka upp igen när röret ställdes vertikalt igen. Därför måste denna luft skilja sig från den luft vi andas, särskilt som den luft vi andas inte kunde passera genom rörets glasvägg. Därför, drog Noël (och Descartes) slutsatsen, måste denna luft vara tillräckligt ”subtil” för att kunna passera genom små porer som med nödvändighet måste finnas i glaset.

En perfekt slutledning från falska premisser! Precis som Fermats korrespondens om optik som Ross presenterar för oss i sin bok, är korrespondensen mellan Pascal och Noël så komisk att den verkligen förtjänar att översättas till engelska.

Varför vägrade Noël att acceptera att utrymmet i röret var tomt? Därför att, sade han, ljus uppenbarligen passerar genom glaset och genom det utrymme från vilket kvicksilvret lämnade. Därför kunde det inte finnas något tomrum på den platsen, eftersom tomrum inte kan ha en fysisk egenskap som att låta ljus passera. Pascal försökte förgäves förklara att vakuum och intet inte är samma sak, trots att vakuum inte är ett ämne och att dess sanna natur ännu inte upptäckts, men Noël ville inte erkänna att denna nya entitet inte kunde identifieras med en existerande.

Den store Descartes lyckades inte heller imponera på den unge Pascal, som senare noterade i sina Pensées (Tankar): ”Descartes är värdelös och osäker.”

Bidrag från Pascal, Huygens och Leibniz

I slutet av sin bok har Ross klokt nog inkluderat texter av Fermat om hans metod för att hitta maxima och minima, vilket förebådade den differentialkalkyl som Leibniz senare skulle uppfinna. Jag skulle vilja tillägga att Pascal å sin sida underlättade användningen av metoden med odelbara tal, som förebådar Leibniz integralkalkyl (motsatsen till differentialkalkyl). För att främja indivisibelmetoden utlyste Pascal en tävling där han utmanade den tidens geometrer att lösa en rad problem rörande rouletten, en geometrisk kurva som idag kallas cykloiden. För att lösa dessa svåra problem krävdes att man behärskade den här typen av beräkningar. Några vetenskapsmän kom med originella lösningar, bland annat den unge Huygens. Pascal publicerade sin egen i sin Treatise on the Roulette.

Att bekämpa cartesianismen var utan tvekan en svår prövning för Huygens, eftersom hans far hade varit en personlig vän till den berömde franske filosofen, som Christiaan hade uppfostrats till att respektera. Ändå insåg han ganska tidigt att de olika lagar som Descartes hade ställt upp för fysiken vid elastiska kollisioner inte stämde överens med varandra, och nästan alla visade sig vara falska.

För att motbevisa dem utvecklade Huygens sin egen relativitetsprincip. Enligt denna princip är fysikens lagar desamma för en observatör som står på stranden av en flod och för en observatör som rör sig med jämn hastighet ombord på en båt på floden. Med utgångspunkt från denna hypotes och den enda korrekta lag som Descartes lade fram (att när två identiska bollar som rör sig mot varandra med samma hastighet kolliderar, studsar de efter kollisionen i motsatta riktningar med samma hastighet), upptäckte Huygens lagen om elastiska kollisioner för det allmänna fallet (där de två bollarna inte är identiska och deras hastigheter är olika).

När han senare skrev sin Treatise on Light lade Huygens fram hypotesen, som bekräftades långt efter hans död, att ljuset är en våg. Denna hypotes har naturligtvis ingenting att göra med de bollar och racketar som Descartes hittade på för att beskriva ljuset, vilket vi får se i den här boken. Men ännu viktigare är att den gör det möjligt för oss att härleda sinusrefraktionslagen från hypotesen att ljus färdas snabbare i luft än i vatten, vilket stöder Fermats princip om minsta tid.

Leibniz och principen om minsta möjliga verkan

När Leibniz anlände till Paris 1672 var det med avsikten att umgås med den tidens främsta vetenskapsmän för att lära sig matematik av dem och på så sätt bli en stor forskare. Satsningen lönade sig. Tre år senare uppfann han differentialräkningen, som revolutionerade hela vetenskapen. På Académie des Sciences fick han av Huygens arvet från Fermat och Pascal, som han fruktbart byggde vidare på.

År 1684 publicerade han i Acta Eruditorum grundtexten till sin nya kalkyl: ”Nova methodus pro maximis et minimis” (”Ny metod för maximi- och minimimått”). För att illustrera kraften i denna uppfinning genom en konkret tillämpning visade han att man, från hypotesen att ljuset sprider sig enligt Fermats princip om minsta tid, kan härleda den berömda sinusrefraktionslagen på bara några rader, på ett sätt som är anmärkningsvärt likt Fermats analytiska demonstration.

Med denna artikel intog Leibniz implicit en anti-cartesiansk hållning. Från och med publiceringen 1686 av sin artikel ”Brevis demonstratio erroris memorabilis Cartesii” (”Kort demonstration av ett anmärkningsvärt fel hos Descartes”) angrep han Descartes fysik mer öppet och antog Huygens tillvägagångssätt i frågan om elastiska kollisioner. Han visade att om Descartes rörelselagar var korrekta skulle en evig mekanisk rörelse vara möjlig – en absurditet som inte ens cartesianerna kunde acceptera.

Under de följande åren ägnade han sig åt en förödande vederläggning av inte bara Descartes vetenskapliga teorier utan framför allt av Descartes metafysiska system som teorierna byggde på.

Genom att generalisera principen om minsta tid som Fermat hade ställt upp som hypotes för sin studie av ljus, etablerade Leibniz den universella principen om minsta verkan, som han till exempel uttryckte på följande sätt i sina New Essays on Human Understanding: ”Naturen agerar på de kortaste vägarna, eller åtminstone på de mest bestämda.” Fermats, Pascals, Huygens’ och Leibniz’ gemensamma ansträngningar befriade alltså det vetenskapliga tänkandet från det cartesianska deduktiva fängelset.

Induktionens mentala återvändsgränd

Samtidigt uppstod emellertid en annan mental återvändsgränd: efter deduktionen kom induktionen. Denna senare metod, som till synes är diametralt motsatt den förra, utvecklades i England av empiristerna Francis Bacon (1561-1625), John Locke (1632-1704) och, framför allt, Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

Till skillnad från deduktion bygger induktion inte på ”uppenbara sanningar” utan på ”objektiva fakta”. Enligt denna doktrin måste forskare göra ett mycket stort antal observationer av naturfenomen, samtidigt som de förbjuder sig själva att ha förutfattade meningar om ämnet.Först efter att ha samlat in en stor mängd data bör forskaren försöka fastställa allmänna matematiska lagar som gör det möjligt att förutsäga observationer och data. Här är det förbjudet att söka orsakerna till fenomen; Newton skulle som bekant förklara: ”Jag ställer inga hypoteser.”

I själva verket är induktion lika steril som deduktion. För det första för att det inte finns något sådant som ett ”objektivt faktum”, eller en observation som görs oberoende av observatörens sätt att tänka. Empiristen som observerar ställer alltså hypoteser, vare sig han är medveten om det eller inte, och finner sig därför a priori oförmögen att hålla fast vid sin egen filosofi. Men det finns en större fråga: Sanna vetenskapliga revolutioner uppstår när individer har modet att förkasta allmänt accepterade självklara sanningar, vilket kräver att man formulerar nya hypoteser. Empirism är därför inte den experimentella metod som uttryckligen använder sig av hypoteser, som vi tidigare beskrivit. En fysikalisk hypotes går längre än att ”rädda utseendet” och anger orsaken till det som observeras.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Utskrift av samma artikel finns nedan på engelska:

This article appears in the December 20, 2024 issue of Executive Intelligence Review.

BOOK REVIEW

Pierre Fermat: Ending the Tyranny of Descartes and the Cartesians

by Pierre Bonnefoy

[Print version of this article]

The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes

A Sourcebook on Pierre de Fermat’s Principle of Least Time

Jason Ross, editor and translator

November 22, 2024

Hardcover, 280 pp., $39.95

Dec. 12—We publish here, with permission, the afterword to Jason Ross’s The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes, A Sourcebook on Pierre de Fermat’s Principle of Least Time. Pierre Bonnefoy’s afterword is a masterful summary of the book that goes beyond a mere review, situating Fermat’s work amidst the battle within science at the time and laying out how later discoveries by Christiaan Huygens and Gottfried Leibniz built upon Fermat’s scientific breakthroughs.

The Battle for Light is the first comprehensive English translation of Fermat’s complete correspondence on light, featuring his landmark disputes with René Descartes, whose explanation of refraction Fermat found totally unconvincing. It presents Fermat’s complete correspondence on light, alongside the Dioptrics of René Descartes and the work of Marin Cureau de la Chambre, whose idea of “least distance” catalyzed Fermat’s formulation of least time. Ross’s translations, presented along with their historical context, offer a fascinating glimpse into the debates that shaped the progress of physical science. Ross’s sourcebook also includes Fermat’s groundbreaking work on finding minima and maxima—which allowed him to precisely calculate the angles of refraction generated by his principle of least time, and which was a key inspiration to Leibniz’s development of the infinitesimal calculus.

When my friend Jason Ross invited me to write the afterword for his book on a fundamental philosophical and scientific battle that took place in my country, France, nearly four centuries ago, I accepted with great pleasure, because this task allows me to highlight, in passing, that not all French people deserve the bad reputation sometimes attributed to them—that they are all Cartesians. On the contrary, some of my illustrious compatriots have fought against Cartesianism, as we have seen in the preceding pages.

The Historical Context: Fermat vs. Descartes

The quarrel between Pierre Fermat (1601-1665) and René Descartes (1596-1650), which Ross has unveiled in this work by relying on original texts, represents an important historical episode that made 17th-Century France the beacon of science in Europe. This was notably reflected in the establishment of the Académie des Sciences in Paris in 1666 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683). More intelligent than many of today’s Western politicians, Colbert appreciated the value of uniting scientists globally, transcending political divides.

However, merely gathering scientists together does not guarantee a harvest of discoveries; there must also exist, in their mutual interactions, an honest search for truth. This requires a certain courage—courage to stand up when one realizes that all one’s colleagues are mistaken on an issue. Being honest in such an environment means daring to confront the sacrosanct “scientific consensus.”

In reality, this problem arises in all times and places—including our own era. But it is unlikely that French science could have played its leading role had not a few particularly courageous individuals, among whom Fermat stands as a pioneer, dared to attack the scientific dogmas imposed by Descartes and the Cartesians. Among these individuals, we must especially mention Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), who maintained a friendly and scientific correspondence with Fermat, although they never met; the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), who directed Colbert’s Académie des Sciences; and the German Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), who, by building upon the discoveries of his predecessors, achieved a scientific revolution by inventing the differential calculus.

portrait by Robert Lefevre

Pierre Fermat (1601-65)

Cartesian Deduction vs. Creativity

These men’s opposition to Descartes was not limited to refuting scientifically false Cartesian theories, but concerned a more profound difference in the approach employed by the researcher to discover the unknown. The fundamental problem of Cartesianism lies not in its specific theories but in its method of thinking.

Probably convinced that he had made great scientific discoveries, Descartes wrote his Discourse on the Method to show how he had proceeded, doubtless hoping to inspire his disciples to become great discoverers themselves. At the heart of this method is deduction. Descartes asserts that the scientist must first base himself only on truths so evident that they cannot be doubted. Each complex problem must then be decomposed into simpler parts, solved individually through chains of deductions that start from previously admitted or demonstrated truths, to arrive at a solution. Descartes claimed to discover the laws of the universe through reasoning alone, without the need to test theories against experience.

Did he know that his method condemned him to discover only what was already known or assumed to be known? In optics, the mathematical law that describes the refraction of a light ray passing through different media—the sine law of refraction—is still sometimes known as the “Law of Descartes”; yet Ross’s book shows us that if Descartes really had discovered this law, we could deduce that he was not a practicing Cartesian himself! Indeed, the “explanations” he provided for the phenomenon are so fanciful that we understand them to have been added afterward to an already established mathematical law: he did not arrive at the correct mathematical formula by deduction from evident truths, as his method prescribes. We must conclude that the sine law of refraction was probably established by Willebrord Snell (1580-1626), whom Descartes had known in Holland; Snell could not claim it for himself, because he died before Descartes published his Dioptrique (Dioptrics), the first book to state it.

Fermat, in contrast, did not practice Cartesian deduction but, rather, the experimental method.

This consists of first formulating a general hypothesis and then testing it through a new experiment: If the experiment’s results contradict the hypothesis, then the hypothesis must be abandoned and another sought; if the experiment confirms the hypothesis, then it will be retained to develop a new theory. Of course, this new theory will be adopted only as long as it is not in turn invalidated by another experiment. In other words, the experimental method is based on nothing evident in itself—only on the hypothesis imagined by the scientist—but it constitutes a real wager on the future: The scientist hopes that the result of the experiment will conform to what his hypothesis predicted.

The Principle of Least Time

In the case of light, Fermat hypothesized his principle of least time, according to which light minimizes the time taken to travel from one given point to another. Fermat found that this hypothesis was in agreement with the sine law of refraction, already verified experimentally, which gave him significant weight against the Cartesians, who had no credible theory of their own. It is interesting to note that the experiment that definitively validated Fermat’s hypothesis was carried out long after the deaths of both Fermat and Descartes. According to Fermat, light travels more easily and faster in less dense media and more slowly in denser media, whereas for Descartes, the opposite was true. Since 17th-Century technology could not compare the speeds of light in different media, Fermat left it to future generations to decide between him and Descartes. In the 19th Century, Foucault’s experiment ruled in favor of Fermat: light is indeed faster in air than in water.

However, the Cartesians had imposed such intellectual terror on the scientific community that Fermat’s victory in optics was not sufficient to overthrow their hegemony.

portrait by Frans Hals, 1648

René Descartes (1596-1650)

Pascal’s Experiments on the Vacuum

Other victories were necessary, notably including that of Pascal concerning his experiments on the vacuum. In this case, as in the previous one, Descartes’s deductive method proved incapable of accounting for a phenomenon incompatible with the old theories.

Consider a transparent test tube, at least 760 mm long, completely filled with mercury. It is then inverted so that its opening is immersed in a basin also containing mercury. In this experiment, which foreshadows the invention of the barometer, the mercury is seen to descend in the test tube to form a column that reaches a certain height above the surface of the mercury in the basin. The question that then haunted scientists was: “What is in the tube between the top of the mercury column and the end of the tube?”

A controversy arose through correspondence between Pascal, who had conducted a series of experiments including this one, and a Jesuit father named Étienne Noël, who had been a teacher of Descartes and contested Pascal’s interpretation of his observations.

Noël, like Descartes, based his arguments on an apparently incontestable truth: “Nature abhors a vacuum.” Therefore, there could be no vacuum in the tube above the mercury, and thus the space must contain a substance of some kind. Now, it was “known” at the time that there existed only four elementary substances: earth, water, air, and fire. Therefore, the substance in the tube could only be some compound of these substances, or one of them. Therefore, this substance must be air. Yet, this air offered no resistance to compression, since by sufficiently tilting the tube, one could see it give way to the mercury until it disappeared, and see it reappear when the tube was set vertical again. Therefore, this air must be different from air we breathe, especially since the air we breathe could not pass through the glass wall of the tube. Therefore, concluded Noël (and Descartes), this air must be sufficiently “subtle” to be able to pass through small pores that must necessarily exist in the glass.

A perfect deduction from false premises! Just like the correspondence of Fermat on optics that Ross presents to us in his book, the correspondence between Pascal and Noël is so comical that it truly deserves to be translated into English.

Why did Noël refuse to accept that the space in the tube was empty? Because, he said, light obviously passes through the glass and through the space from which the mercury departed. Therefore, there could not be nothingness at that place, for nothingness cannot have a physical property like allowing light to pass. Pascal tried in vain to explain that the vacuum and nothingness are not the same thing, even though the vacuum is not a substance and its true nature remained to be discovered, but Noël would not acknowledge that this new entity could not be identified with an existing one.

The great Descartes also failed to impress the young Pascal, who later noted in his Pensées (Thoughts): “Descartes useless and uncertain.”

Contributions of Pascal, Huygens, and Leibniz

At the end of his book, Ross has wisely included texts by Fermat on his method for finding maxima and minima, which foreshadowed the differential calculus that Leibniz would later invent. I would add that Pascal, for his part, facilitated the use of the method of indivisibles, which foreshadows Leibniz’s integral calculus (the reciprocal to differential calculus). To promote the indivisibles, Pascal launched a competition in which he challenged the geometers of his time to solve a series of problems concerning the roulette, a geometric curve now known as the cycloid. Solving these difficult problems required mastering this kind of calculation. Some scientists produced original solutions, including the young Huygens. Pascal published his own in his Treatise on the Roulette.

Fighting Cartesianism was undoubtedly a difficult ordeal for Huygens, for his father had been a personal friend of the famous French philosopher, whom Christiaan had been raised to hold in respect. Nevertheless, he realized fairly early that the various laws that Descartes had stated for the physics of elastic collisions were inconsistent with each other, and almost all were shown to be false.

To refute them, Huygens developed his own principle of relativity. According to this principle, the laws of physics are the same for an observer standing on the bank of a river and for an observer moving at a uniform speed aboard a boat on the river. Starting from this hypothesis and from the only accurate law Descartes put forward (that when two identical balls moving towards each other at the same speed collide, they rebound after the collision in opposite directions at the same speed), Huygens discovered the law of elastic collisions for the general case (in which the two balls are not identical and their speeds are different).

When he later wrote his Treatise on Light, Huygens put forward the hypothesis, validated long after his death, that light is a wave. This hypothesis obviously has nothing to do with the balls and rackets conjured up by Descartes to describe light, as we see in this book. But, more importantly, it allows us to derive the sine law of refraction from the hypothesis that light travels faster in air than in water, which supports Fermat’s principle of least time.

Leibniz and the Principle of Least Action

When Leibniz arrived in Paris in 1672, it was with the intention of associating with the best scientific minds of the time to learn mathematics from them and thus become a great scholar. The gamble paid off. Three years later, he invented the differential calculus, which revolutionized all of science. At the Académie des Sciences, he received from Huygens the heritage of Fermat and Pascal, which he fruitfully built upon.

In 1684, he published in the Acta Eruditorum the founding text of his new calculus: “Nova methodus pro maximis et minimis” (“New Method for Maxima and Minima”). To illustrate the power of this invention through a concrete application, he showed that, from the hypothesis that light propagates according to Fermat’s principle of least time, one can derive the famous sine law of refraction in just a few lines, in a way that is remarkably similar to Fermat’s analytical demonstration.

With this article, Leibniz implicitly took an anti-Cartesian stance. Starting from the publication in 1686 of his article “Brevis demonstratio erroris memorabilis Cartesii” (“Brief Demonstration of a Notable Error of Descartes”), he attacked Descartes’s physics more openly and adopted Huygens’s approach on the question of elastic collisions. He showed that if Descartes’s laws of motion were correct, perpetual mechanical motion would be possible—an absurdity that even the Cartesians could not accept.

In the following years, he engaged in a devastating refutation of not only the scientific theories of Descartes but especially the metaphysical system of Descartes upon which the theories were based.

Generalizing the principle of least time that Fermat had hypothesized for his study of light, Leibniz established the universal principle of least action, which he stated, for example, in his New Essays on Human Understanding, as follows: “Nature acts by the shortest ways, or at least by the most determined ones.” Thus, the combined efforts of Fermat, Pascal, Huygens, and Leibniz liberated scientific thought from the Cartesian deductive prison.

The Mental Dead-End of Induction

However, another mental dead-end arose at the same time: after deduction came induction. This latter method, seemingly diametrically opposed to the former, was developed in England by the empiricists Francis Bacon (1561-1625), John Locke (1632-1704), and, most significantly, Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

Unlike deduction, induction is not based on “evident truths” but on “objective facts.” According to this doctrine, scientists must make a very large number of observations of natural phenomena, while forbidding themselves to have preconceived ideas on the subject. Only after gathering an extensive amount of data should the scientist attempt to state general mathematical laws that allow the prediction of observations, of data. Here, seeking the causes of phenomena is forbidden; Newton would famously declare, “I frame no hypotheses.”

In reality, induction is just as sterile as deduction. Firstly, because there is no such thing as an “objective fact,” or an observation made independently of the observer’s way of thinking. The empiricist who observes thus makes hypotheses, whether he is aware of it or not, and therefore finds himself a priori unable to adhere to his own philosophy. But there is a greater issue: True scientific revolutions occur when individuals have the courage to reject commonly accepted self-evident truths, which requires formulating new hypotheses. Empiricism, therefore, is not the experimental method that explicitly employs hypotheses, as we previously described. A physical hypothesis goes beyond “saving appearances,” to state the cause of what is observed.

Ross explains how Fermat’s 17th-Century discoveries challenge crucial assumptions about natural processes and scientific method that you have been taught. Here, editor and translator Jason A. Ross at the Fermat Museum in Toulouse, France, November 2024.

It is by hypothesis that the experimental method studies the causes of phenomena, while empiricists, deprived of hypotheses, must content themselves with seeking to predict effects. Yet, although effects are observable, causes generally are not. Therefore, through simple induction, one cannot ascend to these principles, such as that of least time or least action, which have revolutionized science beyond the mere question of the refraction of light.

This issue, which is significant for contemporary science, warrants further argument, but this would go beyond the scope of this afterword. I will therefore conclude with some remarks on the myth of Newton as it relates to the work of Fermat and his successors.

The Myth of Newton

In his Opticks, Newton puts forward a corpuscular theory of light, which constitutes a real regression from the works of Huygens, with which he was familiar. Yet Newton’s theory dominated the 18th Century. One of its notable tenets is that light moves faster in denser media and slower in less dense media.

Seeking to undermine Leibniz’s influence, Newton claimed that Leibniz had stolen the invention of differential calculus from him, and launched a veritable trial against Fermat at the Royal Society in London—of which Newton was the president! Today, historians recognize the dishonesty of this trial, as Newton was both judge and a party to the affair, but they nearly all say that Newton and Leibniz independently invented differential calculus: an absurd scientific consensus that is easy to refute. Newton never produced a differential calculus; he produced the “calculus of fluxions,” which no one ever used outside of a few scholars of the Royal Society of his time, because it is in fact impracticable. Even British scholars had to adopt Leibniz’s differential calculus.

Conclusion

What relevance does all this have for us today?

Today, many scientists may struggle to differentiate between the mathematical or computational models they use and genuine physical hypotheses, such as the principle of least time. It is certainly legitimate and even necessary for an engineer to use models in his work. But this is a problem in the case of a researcher who explores the unknown. Models have past theories as their foundation and will never yield anything new. The excessive reliance of today’s scientists on modeling (in quantum physics, economics, climatology, biology, etc.) shows that induction/deduction and empiricism, despite their intrinsic limits, have not really been eradicated. To solve this problem, we must study the history of science from original texts and through the original controversies, and not only by reading academic commentaries.

We must draw inspiration from scholars who, like Fermat, overturned established knowledge through revolutionary hypotheses.

This is the approach that Ross, through his work, has invited us to take.